Climate change is ‘off the charts’ and presents a ‘defining challenge’ to humanity, a damning new report warns today.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) says several climate records were broken and in some cases ‘smashed’ last year.

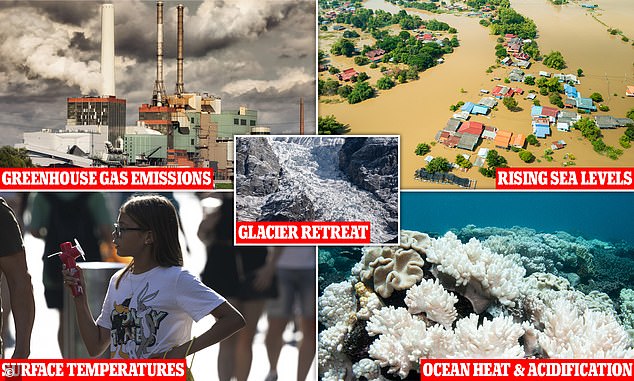

Greenhouse gas levels, surface temperatures, ocean heat and acidification, sea level rises, and Antarctic ice loss all escalating in 2023 due to fossil fuel emissions.

‘Sirens are blaring across all major indicators,’ said United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres.

‘Some records aren’t just chart-topping, they’re chart-busting – and changes are speeding-up.’

From greenhouse gas emissions to air surface temperatures, climate change indicators reached record levels in 2023

The WMO’s State of the Global Climate report, published today, confirms that the year 2023 broke ‘every single climate indicator’.

TEMPERATURES

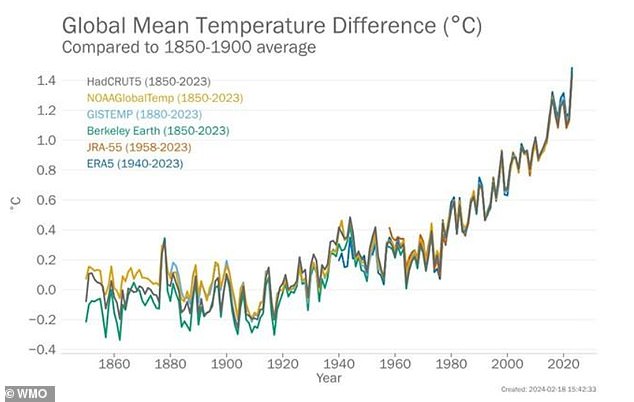

WMO confirmd that 2023 was the warmest year on record, as already announced by the UN’s Copernicus climate change programme in January.

The global average near-surface air temperature for the year was at 2.61°F (1.45°C) above the pre-industrial average (1850 to 1900).

Before 2023, the two previous warmest years were 2016 (2.32°F/1.29°C above the 1850–1900 average) and 2020 (2.28°F/1.27°F above the 1850–1900 average).

What’s more, the past nine years – between 2015 and 2023 – were the nine warmest years on record.

But the experts admit that the shift to ‘El Niño’ conditions in the middle of 2023 contributed to a rapid rise in temperature from 2022 to 2023.

El Niño is natural climate phenomenon where there’s warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean near the equator.

This graph shows annual global mean temperature anomalies (relative to 1850–1900) from 1850 to 2023. Data is from six temperature data sets, including the UK Met Office’s HadCRUT5

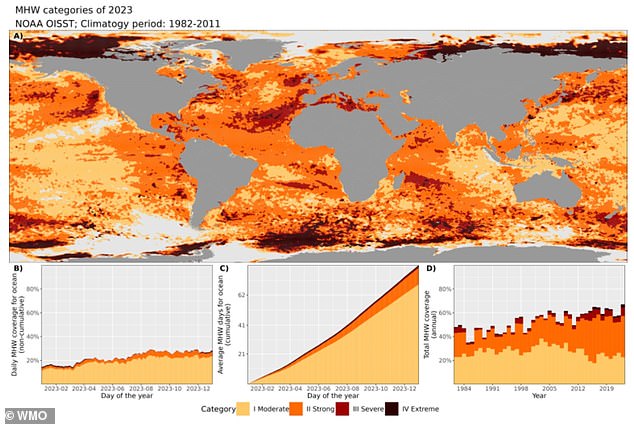

Global map of the planet’s oceans, showing the highest marine heatwaves in 2023, from moderate in yellow to extreme in dark brown

GREENHOUSE GASES

Temperatures are largely fueled by greenhouse gas emissions, and these continued to climb in 2023.

WMO says data for concentrations of the three main greenhouse gases in the air (carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide) are not yet available for the whole of 2023, but in 2022 they reached ‘new highs’.

Globally averaged concentrations were 417.9 parts per million (ppm) for carbon dioxide (CO2), 1,923 parts per billion (ppb) for methane (CH4), and 335.8 ppb for nitrous oxide (N2O).

Respectively, this marks an alarming rise of 150 per cent, 264 per cent and 124 per cent compared with greenhouse gas concentrations levels in the year 1750.

‘For more than 250 years, the burning of oil, gas and coal has filled the atmosphere with greenhouse gasses,’ said Dr Friederike Otto, climate lecturer at Imperial College London, who wasn’t involved in the report.

‘The result is the dire situation we are in today – a rapidly heating climate with dangerous weather, suffering ecosystems and rising sea-levels, as outlined by the WMO report.

‘To stop things from getting worse, humans need to stop burning fossil fuels. It really is that simple.

‘If we do not stop burning fossil fuels, the climate will continue to warm, making life more dangerous, more unpredictable, and more expensive for billions of people on earth.’

OCEAN HEAT

Although the main metric for measuring how hot the planet is getting is air temperatures, WMO also tracks how hot the world’s waters are getting.

Numerous adverse effects result from ocean warming, including accelerated melting of Earth’s ice sheets and sea level rise due to thermal expansion.

Ocean species are also threatened, including coral which become ‘bleached’ white due to the stress of higher temperatures.

When the ocean environment changes – if it gets too hot, for instance – coral stresses out and expels algae which makes it turn white. Pictured, coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef during a mass bleaching event in 2017

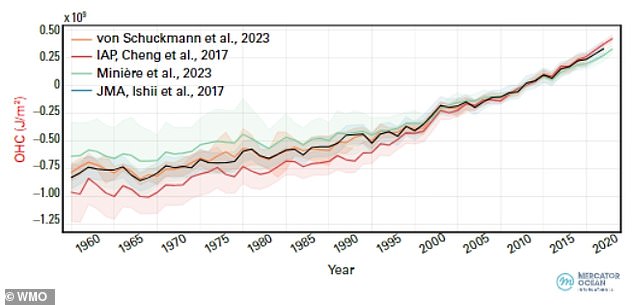

This graph shows anomalies in the heat of Earth’s oceans (relative to the 2005–2021 average) between 1960 and 2023

Meanwhile, CO2 dissolving in the ocean causes acidification of the waters, which makes it harder for marine life such as lobsters, shrimp and coral reefs to survive.

WMO says the overall temperature of Earth’s oceans have risen since 1960 and ‘it is expected that warming will continue’.

The Southern Ocean is the largest reservoir of heat, accounting for around 32 per cent of the ocean heat increase since 1958.

The Atlantic Ocean accounts for around 31 per cent, while the Pacific Ocean makes up around 26 per cent.

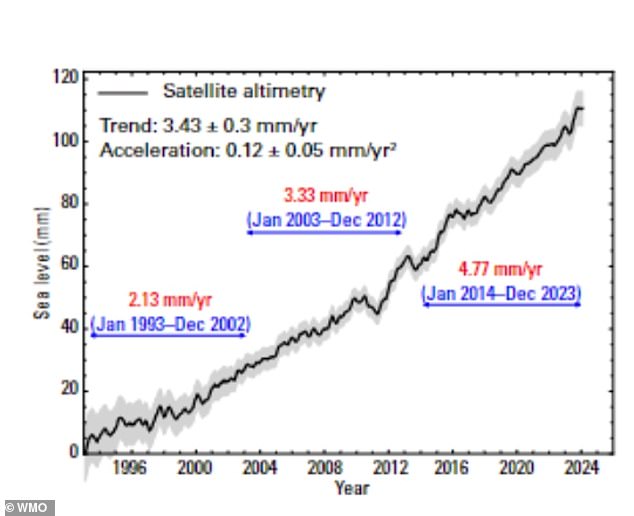

SEA LEVELS

Rising sea levels can cause disastrous flooding, forcing authorities to spend millions on flood defences and even force people to flee their homes.

This is largely being caused by the increased melting of land-based ice, such as glaciers and ice sheets.

Again, in 2023, global mean sea levels reached a record high since they first started to be tracked with satellites, in 1993.

Fossil fuels (coal, oil and gas) are the largest contributor to global climate change, accounting for over 75 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the UN

Rising sea levels can cause disastrous flooding, forcing authorities to spend millions on flood defences and even force people to flee their homes. Pictured, flooding in Thailand

Graph shows the global average rise in sea levels since they first started to be tracked with satellites, in 1993

According to the WMO, average sea level rises went from 0.08-inch (2.13mm) per year between 1993 and 2002, to 0.13-inch (3.33mm) per year between 2003 to 2012, and finally 0.18-inch (4.77mm) per year between 2014 and 2023.

Although this may not sound like much, Professor Jonathan Bamber, director of the Bristol Glaciology Centre at the University of Bristol, said this could lead to catastrophic long-term change.

‘Our own research indicates that, if greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, there is a small chance that we could experience up to a 2 metre rise by 2100,’ he said.

‘This would truly be catastrophic for civilisation with the potential to displace around a tenth of the population of the planet.

‘We are looking at the disappearance of small island nation states in the not too distant future and inundation of heavily populated coastal zones.’

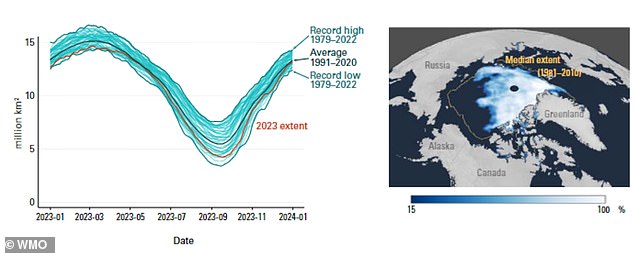

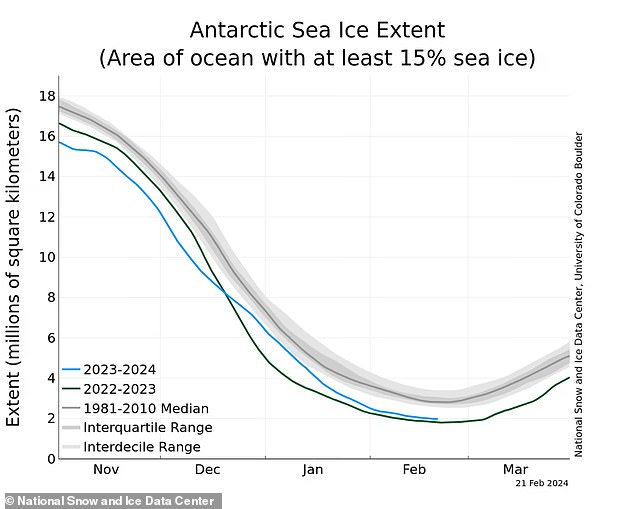

MELTING ICE

Due to the higher surface and ocean temperatures, ice in the Antarctic reached a record low since records began in 1979.

September’s annual maximum – when Antarctic ice is usually at its greatest extent due to colder temperatures – was 6.54 million sq miles (16.96 million sq km).

This is roughly 5.7 million sq miles (1.5 million sq km) below the 1991-2020 average and 386,000 sq miles (1 million sq km2) below the previous record low maximum.

In the northern hemisphere meanwhile, the Greenland Ice Sheet – the world’s second-biggest ice sheet after Antarctic – continued to lose mass in 2023.

Combining the two ice sheets, average rates of mass loss increased from 105 gigatonnes per year from 1992-1996 to 372 gigatonnes per year from 2016–2020.

Sea ice plays an important role maintaining the Earth’s energy balance while helping keep polar regions cool due to its ability to reflect more sunlight back to space. Pictured, sea ice in the water off Cuverville Island in the Antarctic

Left graph shows daily Arctic sea-ice extent from January through December, showing 2023 (red line) against the climate normal (1991–2020, dark blue) and the record highest and lowest extents for each day (mid blue). Right image shows ice concentration on September 19, 2023, at the annual minimum Arctic ice extent. The yellow line indicates the median ice edge for the 1981–2010 period

The world’s glaciers – which reflect sunlight back into space and help keep the planet cool – likely suffered ‘the largest loss of ice on record’ since 1950.

In Switzerland, which relies on ice for the ski season, glaciers have lost around 10 per cent of their remaining volume in the past two years.

‘If that trend continues then we could see much of the Alps devoid of glaciers in a matter of decades,’ said Professor Bamber.

‘That is something that few, if any of us, would have expected see happen so rapidly.’

Climate scientists are constantly tracking sea ice extent throughout the seasons and comparing its size with the same months from previous years, in order to see how it’s changing. Data from National Snow and Ice Data Center has recently showed that sea ice extent is lower than the average since records began, regardless of time of year

A glacier is an accumulation of snow compacted over thousands of years to become solid ice. Glaciers are important sources of water as they hold about two-thirds of the Earth’s freshwater. Pictured, the Langtang Glacier in Nepal

Researchers also warn that extreme weather events including floods, tropical cyclones, drought, and wildfires, are linked with the warming of the planet and so will likely keep occurring.

These will hit ‘vulnerable populations’ in countries without the ability to respond adequately already hit by food insecurity, such as Somalia, Sudan and Syria.

‘Climate change can intensify existing inequalities and social and economic pressures, placing further pressure on the people and places who are already under stress and who have often done the least to cause climate change in the first place,’ said Dr Leslie Mabon, lecturer in environmental systems at The Open University.

Professor Tina van de Flierdt, head of the Department of Earth Science and Engineering at Imperial College London, called the new report ‘alarming’.

‘Generally, the data in the report reinforces that climate change is not a distant threat – it is here now, and it is already impacting lives worldwide,’ she said.

‘However, it is important to note that we are not yet locked into this trajectory.

‘The future is in our hands, and ongoing climate projects and greater use of clean energy sources offer hope for a just and resilient future.’