Every time Caroline McClarin wakes up, she gives herself an hour before she can leave her bed.

A shower takes about 40 minutes, depending how painful her legs are.

Born with talipes (club foot) and always prone to bruising easily, 49-year-old McClarin has undergone decades of testing in an attempt to explain her various – and seemingly disconnected – conditions.

There are those linked to the endocrine system (polycystic ovary syndrome and thyroid problems); the half-closed, half-open eyes during sleep; unexplained hair loss; mini strokes; and coughing fits so bad she often passes out.

“I have been in a specialist ENT office and literally passed out after a coughing fit,” she says.

“Yet all the tests they did had looked into normal conditions and came up with nothing.

“My doctor actually said, ‘we’ve seen you have a coughing fit, we just don’t know what to look for’”.

When she was 17, McClarin was even tested for leukaemia after suddenly losing all her hair.

Finally, aged 39, and following a collapse in hospital during a night shift working as a lab assistant, a visiting UK doctor ordered McClarin to be tested for vEDS – vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome – a subtype of a little-known condition that is extremely complex, debilitating and, until recently, thought to be very rare.

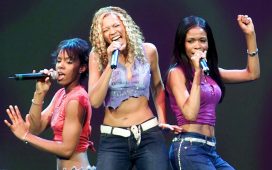

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes are 13 heritable (genetic) connective tissue disorders affecting the quality of collagen in every part of the body. Last month the singer Sia Furler revealed she had EDS, casting a rare spotlight on a little-known condition.

Men and women are equally at risk of inheriting the conditions, but their effects tend to be more severe for women.

The most common form, hypermobile EDS (hEDS), accounts for about 80% of the EDS population, and is characterised by extremely bendy joints, making them more likely to be dislocated or sprained.

Those with the most dangerous subset, vascular EDS, such as McClarin, have a significantly shortened life expectancy because they are more likely to die from ruptured aortas, ruptured bowels and brain haemorrhages.

EDS has a tendency to branch out and affect multiple bodily systems, causing seemingly unrelated systems that make it very difficult to diagnose.

In Australia, EDS is classified as a rare disease, meaning it does not have its own Medicare number and is rarely recognised by most GPs and specialists. The Department of Health does not collect data on EDS.

But a new study, published in BMJ Open on Tuesday, shows that even the number of those who have been diagnosed with EDS may be much higher than previously thought.

After looking at all GP and hospital records in Wales between 1990 and 2017, UK researchers identified 6,021 people diagnosed with EDS – closer to 1 in 500, or 0.2%, rather than the currently cited statistic of 1 in 5000.

“This shows that these conditions are actually not rare,” says Dr Emma Reinhold, a GP and co-author of the study.

Recent research taking into account those living with the condition but with no diagnosis estimates the “true prevalence of symptomatic generalised joint hypermobility lies between 0.75 and 3.4% of the population”, Reinhold says.

The BMJ Open study found most men (72%) with the condition are diagnosed when they are under 18, but only 41% of women.

Researchers speculate this may be due to the assumption that women are naturally more flexible than men, therefore dismissing potential causes of hypermobility disorders.

Failure to diagnose the condition in adulthood may reflect medical systems that are inherently biased against female patients.

Countless studies show that women are often dismissed and ignored by the medical system, and that their pain is more often “minimised and psychologised”. Earlier this year, a Danish study found that women were diagnosed with diseases an average of four years later than men.

That is especially true for women who suffer from rare, little-known or misunderstood conditions.

“A lot of women with EDS say they stop seeing doctors as it can feel too traumatic and often pointless,” Reinhold says. “As a result, women are avoiding getting the care they desperately need.”

Emeritus professor David Sillence and his team at the children’s hospital in Westmead, Sydney, developed the first clinic in Australia specifically for people with EDS and related connective tissue disorders. Since then he has diagnosed thousands of children and, as a consequence, their parents.

“Many parents come to us and when we diagnose their child and adolescents, they realise they have been trying to deal with the same disorder,” he says.

He says men and women both suffer from issues such as stress incontinence, chronic fatigue, chronic musculoskeletal pain, sprains, bruising and blood vessel fragility, but female EDS sufferers tend to have more complications due to physiological changes during monthly cycles and during a pregnancy.

“I have had women who informed me in their 50s that since teenage years, they’ve had to carry a pad with them as they have had stress incontinence every time they played sports,” he says.

There is no effective treatment for EDS, although for most subtypes symptoms can be prevented or reduced with the help of a physiotherapist skilled in pelvic floor management.

Many people live with the condition for up to 20 years before finding a diagnosis.

“For me, a patient who comes in citing chronic fatigue, medically unexplained symptoms and – especially for women – fibromyalgia, already has my antenne twitching,” Reinhold says.

“The second sign is recognising the pattern of multiple seemingly unconnected diagnoses and symptoms. There’s this saying we use: if you can’t connect the issues, think connective tissues.”

Rona Torrance runs the group Ehlers Danlos Support Group Australia. Now in her 50s, she was first diagnosed in her native UK when she was 18 – something she says is very rare in Australia.

It was only eight years ago that she finally met another woman with the condition.

Torrance says most sufferers are eventually diagnosed because of their hypermobility, but not all EDS cases present with those symptoms.

“It’s such a collection of things you wouldn’t necessarily put together, so we often get misdiagnosed,” she says. “At one stage I was speaking to five different specialists who knew nothing about the disorder.”

Torrance says those with EDS would have more access to funding if it was officially recognised as a disability. Financial stress compounds the debilitating physical and psychological consequences of EDS, she says.

“So many of us have to live in constant fear of spontaneous ruptures and the possibility that even the simplest bleed can kill us.”

For McClarin, this is the everyday reality. She is unable to look after herself and lives with her 73-year-old mother, who is her full-time carer.

“If Mum passes before me, I’m going to have to go into assisted living – I can’t look after myself,” she says.

“At 49, this shouldn’t be my reality – and that plays on my mind a lot.”