‘In my childhood, cinema was like going into a temple. Now, it’s more like going into a shopping mall,” says Tsai Ming-liang. Over the course of his nearly 30-year career, the Taiwanese film-maker’s work has moved further and further towards the “temple” end of the spectrum. Often bracketed under the “slow cinema” movement, he is a master of the very long take. His last feature, 2013’s Stray Dogs, included a shot of two people staring at a mural in an abandoned building that lasted over 14 minutes. But despite his shaven head, Tsai is no monk. In the past, his films have featured choreographed musical sequences, surreal comedy, and plenty of sex – gay, straight, solo, even watermelon-incorporating, in the case of 2005’s The Wayward Cloud.

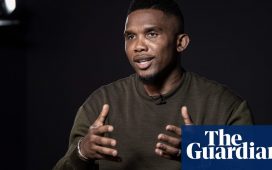

In person, he is unassuming and quick to laugh. “In the past I really cared if people understood my films, but when you grow older, you care less,” says Tsai, who turned 61 last year. “You want to do something to please yourself. I feel like the film industry has trapped film-makers. They tell you you need to have a narrative structure, you need to do things a certain way. They limit the imaginations of film-makers. I often think about, what is the meaning of film? What does film want to say? The simple thing is, film is about images.”

After Stray Dogs, which won a host of international awards, Tsai claimed he was giving up commercial cinema altogether, but few could have anticipated where he would go next: virtual reality. The Deserted is possibly Tsai’s most contemplative work yet. Free of dialogue and narrative, it is set in a derelict, overgrown apartment block in the Taiwanese countryside, occupied by a man with neck pains, and what could be the ghosts of his mother and wife, and a large, white pet fish. The viewer becomes an invisible spectator to this surreal domestic tableau. The action is unhurried but never dull to look at, and you can always swivel round on your chair to appreciate the stained concrete walls, the puddles on the floor and the lush greenery outside the pane-less windows.

Tsai is one of the most consistent auteurs cinema has ever known, and aficionados will recognise many of his trademarks in The Deserted: the man is Tsai’s regular actor Lee Kang-sheng – whom he first cast in 1991, and has not made a film without since; derelict buildings and water also frequently feature in his work. Ghosts, too: in Goodbye, Dragon Inn, the living and the dead communed in a condemned Taipei cinema (screening King Hu’s 1967 martial arts classic Dragon Inn). Lee’s neck pain was also a theme in 1997’s The River. The white fish was also seen in 2001’s What Time Is It There? when the mother believed it to be the reincarnated spirit of her dead husband. The Deserted is a film full of ghosts, and thanks to virtual reality, the viewer becomes another one.

“I’m a Buddhist,” says Tsai. “When I enter a new space, especially ruins or an abandoned place, I often say hello and have a little chat. I always feel there is someone there, a fairy, ghost or spirit.” The Mandarin title of The Deserted translates as The Home at Lan Re Temple, Tsai explains, which comes from a Chinese ghost story. “The Lan Re temple in Buddhism is actually a space for all the spirits to gather around. This is their space.” The Deserted was shot next door to the abandoned building where Tsai and Lee moved five years ago, to get back to nature and help Lee’s recovery after a stroke and a mystery recurring illness (the neck pain is real). Another recent film, Afternoon, also shot in an abandoned building nearby, is a conversation between the two men, about their long relationship, personal and professional.

“Through film-making, I have discovered the concept of time,” Tsai says. Having worked with the same subjects and casts for decades, his films have become a way of capturing the ghosts of the past and tracking time’s passage, whether in the face of Lee or the landscapes of rapidly developing Taiwan.

Tsai, born in Malaysia, came to Taiwan as a student in 1985 when the country was still under martial law. That ended two years later, and Tsai became part of a new wave of renowned Taiwanese film-makers, including Ang Lee, Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang. They didn’t just benefit from Taiwan’s liberalisation, they helped make it happen, Tsai explains. “Me and many other film-makers were fighting the system, trying to make it more open. If you look at Asia now, Taiwan is the most open-minded and welcoming to all ways of film-making.”

Tsai never stopped making films after Stray Dogs, he says; he just found other ways to do it, and different places to show them. Where his contemporaries have struggled to compete with Hollywood and Chinese blockbusters in the “shopping mall”, Tsai has turned to museums and art galleries to show his work. “Many people tell me I should have disappeared a long time ago,” he laughs. But instead, to his surprise, he has found new viewers. “In Asia right now, my audiences are more people in their teens and 20s than people of my generation,” he says. “Maybe it’s because they are the internet generation, they see so much information every day. So when they experience my films they maybe feel something different. They have no baggage about ‘what is film?’”

As well as honouring cinema’s past, perhaps Tsai’s meditative works points the way to its future.

• A retrospective of Tsai Ming-Liang’s films, curated by the director himself, and including the UK premiere of The Deserted (4-8 April), is part of of the UK Taiwan film festival, from 3-14 April.