Warning: This story contains discussion and description of sexual abuse, assault, and trauma.

When Jay first came into the program, he was asked – as all members were – to share his offense with the group. He said he’d had sex with his teenage stepdaughter.

“She was very attractive,” he said. “Mature for her age. We kind of fell into it.”

One night several months into his treatment, I had a dream. We were in the middle of group therapy. Jay got up, strode across the middle of the group and picked me up with my arms pinned to my sides. I fought with him as he unflinchingly overpowered me and tore off my clothes. I woke up in the dark with my heart pounding, shaken. The rest of the night I tossed and turned, the experience too real to shake.

The next day at the office I went directly to Jay’s file and read carefully through the police reports. I was stunned, yet somehow not surprised, to find that he had raped his stepdaughter. The case had been reduced to sex with a minor as part of a plea agreement.

The shock wasn’t that he had lied, it was more that we hadn’t questioned it sooner. His story had been believable, and his manner seductive. But a quiet part of me, my unconscious mind, had paid attention. It refused to be seduced by him. I will always listen to that part of myself now.

•••

I started my career working with victims of sexual abuse but eventually began working directly with the perpetrators. Later I started evaluating violent sex offenders in California prisons for potential release. It’s a world in which a routine day has me confronted with the darkest and most twisted acts imaginable. And my decisions could mean an offender is indefinitely committed to a mental institution – or that they get released back into society.

I’m often asked how I can stand to face these men. They should be imprisoned for life, publicly identified, barred from common spaces and participation in civic life, right? They should be tarred and feathered, stoned, segregated into a special zone far, far away from our children and loved ones. Even in prison, they inhabit the lowest rung of a brutal hierarchy.

I’ve spent hundreds upon hundreds of hours interviewing these men about their childhoods, their frustrations, their demons and their drives, and the terrible crimes they have committed. Sometimes these interviews are brutal. Sometimes they are tinged with unexpected moments of understanding and compassion. But the truth of my experience is that not all sex offenders are monsters. They are humans – people we may even know and see every day.

And yet, of course, I feel deeply protective of my own family – a paradox I confront again and again as my work uncomfortably collides with my life as a woman, wife, and mother of three.

•••

I’m interviewing James, whose long rap sheet started as a middle schooler and encompasses pimping, stealing, and several sexual assaults. During the interview, he’s a smooth operator; it’s obvious he’s able to talk his way out of trouble most of the time. He gazes at me through lids halfway down, a smile playing on his face. He makes everything an inside joke and laughs easily. But almost nothing he says is funny to me.

Throughout the interview I remain neutral. I want him to talk as openly as possible, so I appear open enough to form a connection, then knock him off balance every now and then with a question he doesn’t expect. I ask him about high school. He says he was pimping by the time he was 16; his cousin initiated him into the business.

“Yeah, I was good,” he brags. “I would bend ’em and send ’em.”

I take this to mean that he had sex with the women who “worked for him” whenever he wanted. I refrain from making a face. I ask him just to be sure. “What exactly does that mean?”

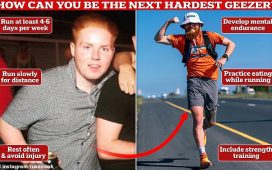

here. Illustration: Anxy Magazine

“I was born hung,” he explains. “I can stick my magic wand in them and show them the ropes before I send them out there to do their thing.”

He goes on like this during the interview, talking with relish about his penis size, his sexual prowess, the ways he’s used women. I’m revolted, but the sexism and misogyny are so extreme it almost seems unreal. I write it all down, thinking about how he’s so caught up in the pleasure of himself that he forgets who he’s speaking to, and the consequences. He speaks to me using my first name. I correct him. He continues to do it anyway.

He keeps talking, looking at me, touching his shirt. It takes me a minute to realize: yes, that really is his erect penis under his shirt. He’s touching himself.

I look directly into his eyes. “Are you stimulating yourself? You need to stop immediately.”

“Nah, nah, I wasn’t doing nothing,” he replies, quickly adjusting his pants, sitting up in his chair.

I take a deep breath and compose myself. My stomach is tight and I’m shaken, but I need to complete this interview; I’ll deal with my feelings later. Honestly, I’m stunned. Not so much that he would do such a thing, but by his lack of control. I could recommend that he gets committed indefinitely based on his sexual behavior, and this is what he chooses to do? For the rest of the interview he refers to me as “Doc” and does not touch himself again.

After the interview I report his behavior to the prison. My final evaluation states that he meets the criteria for a sexually violent predator; his actions were just one more example of how little restraint he has. I think about him even after I’m done: his lack of control, his disregard for women, the audacity to think he can get away with anything, his egoism that I would believe his bullshit stories, his arrogance that I would sit there while he got himself off.

•••

That evening, I head out for a walk after the kids are in bed. I’m stressed – about money, about getting work done, about not having exercised. With three children and a mortgage, there’s never enough time or money. I walk fast to try to get the workout I desperately need, but as I do, I’m aware, as most women would be, of the places the moonlight and streetlamps don’t reach. A lit cigarette in a doorway – is it a man or a woman standing there? I wish it didn’t matter.

I used to run treatment groups for sex offenders. At the time, my work actually made me less afraid. I genuinely liked many of the guys and knew they respected me, even felt protective of me. Walking home afterwards I felt a sense of security – false, perhaps – that I wouldn’t be attacked by a man who knew I had the phone number of his parole officer. I felt, and still feel, safe, comfortable, and at home around men.

But in other ways I’ve become more pessimistic. After reading about hundreds upon hundreds of victimizations, it begins to feel inevitable and unstoppable. Men seem to pose a terrible threat. My husband, my male colleagues, my friends – they all live in the same world with James, Jay, and the others I have to evaluate.

Professionally, though, I know different. Yes, a small percentage of men who commit sex crimes are incapable of empathy; or worse, take pleasure in the suffering of those they violate. But most sex offenders are not psychopaths. They are men raised in a horrible system – frequently having suffered trauma, or abuse, or both – who lack the tools to navigate their emotions, and end up traumatizing others as a result. Or they are men who have paraphilic desires – that is, recurrent, intense, distressing, arousing fantasies that involve objects, suffering, humiliation, children, or a lack of consent –but have too much shame to seek the help they need to make sure they don’t hurt other people.

•••

I’m on my way to interview Leo, a 37-year-old man I last evaluated a year ago. At the time, I decided he met the criteria of a sexually violent predator, but he ended up being released from prison anyway (my opinion is not the only factor taken into account). A year later he was sent back to jail for a minor parole violation, so now he’s being evaluated again – the law requires a fresh decision.

I go expecting to reaffirm my earlier evaluation. It wasn’t especially challenging last time; Leo was full of nervous habits and lied his way through the entire interview. He was suspicious, a drug addict, and a career criminal whose past included several attempted rapes.

But sitting down with him today I’m shocked. He’s a completely different person.

“I’m sorry I’m crying so much,” he says, wiping his face with his sleeve. “My therapist says I’m crying all the time because I’m off drugs for the first time in my life. I’m feeling my feelings now.”

“Your therapist?” I ask, almost disbelieving that this is the same man I met before. A year earlier he would never have gone to a therapist, had feelings, or cried openly.

“Yeah,” he replies shyly, looking down. “He’s really helping me.”

He has tear tattoos, two of them, just below the lower corner of each eye. I don’t ask Leo what they symbolize. Instead I watch the real tears that run alongside them for the entire hour we speak.

“I feel so bad about all I did,” he says, crying again. “I’ve been trying to make up for it. I help people whenever I can. Now that I’m off drugs I feel for people. I feel bad for them. I never felt that before. Sometimes it’s almost too much.”

He talks with pride about how he stayed out of prison for a whole year this time. It’s the longest he’s been out of jail since he was 15.

“I got a real job,” he says, smiling. “I have a car and it’s registered and I have insurance.

“I have a girlfriend, too. I’ve never had a relationship.”

The hour goes by and he is emotional, insightful, and humble. I write it all down. I’m deeply moved by the experience – by the obvious change in him. I want to reverse my original decision, but it doesn’t matter what I want or don’t want. It’s my job to decide objectively. When I get home, I set the interview aside. It feels too sad. I’ll pick it up in a few days.

•••

Most men who commit a sex offense are not irredeemable or unworthy of a future in our society. Having performed therapy with sexual offenders for over a decade, I have been repeatedly surprised at the capacity for change. Not everyone is a James or a Jay.

There are Leos out there too, even if it is hard for us to accept.

Statistics bear out my experience. The number of sex offenders who re-offend is small relative to many other crimes, and the proper treatment – a program that addresses their thinking and behavior directly, and is designed, based on research, to prevent them from offending again – can reduce that number even further. One analysis of treatment studies showed that sex offenders who got treatment were re-arrested only 7.2% of the time, while those who went untreated re-offended at a rate of 17.6%. That’s significant. (By comparison, a 1994 study showed that robbers were re-arrested at a rate of 70.2%, burglars at 74%, and motor vehicle thieves at 78.8%).

•••

For several years I’ve been providing clinical supervision for a woman who’s been treating sex offenders but is still working toward licensure. She’s in her early 30s, living with her fiance, and disarmingly open about her thoughts and feelings. It’s a pleasure for me to offer the space for her to grow and learn about how to do this challenging work. The space between us is warm and honest.

Recently, after we spoke about her patients, there was a pause and she asked, abruptly, “Does this work ever affect your opinion of men?”

She went on to talk about a recent group she had led.

“The men all talked about how at some point in their life they’d had affairs and lied to their partners. I kinda got freaked out and went home and asked my boyfriend if he ever cheated on me. He was like, ‘What? What are you talking about?’ After I explained what had happened he was understanding about it, but the whole thing made me worried about how I was thinking about men – like they’re all kinda out of control sexually.”

I took in what she’d said, reflecting on my own experience. For a moment I considered offering her reassurances, but decided to be honest. “This isn’t an idle worry,” I said, sadly. “Maybe the task isn’t to not be changed; that’s just not possible. Maybe instead it’s to not become jaded. To work to love individual men. And to be able to hold on to compassion for the mistakes of being human.”

“Yeah,” she said. “That makes sense. That’s a goal I can work on.”

The truth is, even good men in my life whom I love and trust have made mistakes along the way, acted unconsciously sexually, and broken trust. I wanted to offer her something certain to hold on to, but all I could think of was to remind her that most sex offenders are men, but most men are not sex offenders.

It’s a message I want to be able to communicate to my children, too, but I’m not sure how to do that while also teaching them about safety.

Instead, I use my knowledge of criminality, statistics, and risk to give them practical advice.

“Tell me if anyone does something that makes you uncomfortable, or touches you in places that are confusing,” I tell them. “Even if it’s a man you know and like, or trust.”

It’s practical – if they are molested it will most likely be by someone they know – but it’s painful. I also use my knowledge to help them safely get help, if they need it. I never tell them: “Don’t talk to strangers.” What if they’re lost and they need help? Instead I tell them: “If you get lost, look for a mommy first; if no mommy is around, look for a woman.”

My children are safer that way, statistically speaking. But of course there is a deeper, implied message: men are more likely to be scary and dangerous. Even if you know them.

I worry what that message will mean to them.

I worry what that message means to me, too.

-

Samantha Smithstein, PsyD, is a licensed Clinical and Forensic Psychologist, writer, and photographer based in San Francisco

This story was first published in Anxy Magazine: The Masculinity Issue. Anxy explores personal narratives through a creative lens