Solomon was my first baby. He was loud. He screamed full throttle for an hour until the midwife swaddled him. I knew he was different from the moment I washed his slick dark hair and saw the ecstasy on his face. At home, he’d stare at his ladybird rattle for 15 minutes at a time. He’d gurgle with delight when we sang to him, but scream frenetically at the noise of the Hoover or blender. At postnatal groups, he’d crawl into a corner, alone.

As a toddler, he learned all his times tables from watching a video repeatedly. He adored Thomas The Tank Engine and could quote from it seamlessly. Solomon had hyperlexia, a precocious reading ability. He was exceptional at maths but also an avid reader. He loved words. He’d make up brilliant, onomatopoeic neologisms to describe facial expressions that amused him (an “agarg” was absolute surprise).

Solomon was diagnosed with autism when he was five. Boys are much more likely to receive a diagnosis than girls; the latest male-to-female ratio is close to 3:1. Boys are also diagnosed earlier. We learned during the process that autism is hereditary. We were asked repeatedly: “Is anyone else in your family autistic?”

No, we replied. Because no one we knew was exceptional at maths and obsessive about trains or had sensory issues so extreme that every family outing had to be meticulously planned, avoiding strip lights and hand driers. But I’ve read recently that autism manifests differently in women, that we’re better at hiding it. Now, some episodes in my family history begin to make sense.

In my mid-30s, pre-motherhood, upstairs on a bus in London, I saw a middle-aged black woman shuffling along the pavement. She looked dishevelled but clean, wearing too many layers of clothing. How rare, I thought, to see a black homeless woman. I was mesmerised by her dignity, wondering if she was OK. Then I felt the lightning bolt of recognition, followed by shame at my error. She was my mother.

But who was she? After leaving my father, my brother and me, my mother lived in Nigeria from when I was 10 to 35, rarely visiting the UK. As early as I can remember, my mother struggled to maintain relationships with family, friends and colleagues because, in her words, “They say I’m eccentric. And bossy.” She was inflexible, seeing everything in black and white. Either she fell out with people, or they fell out with her.

When I was 10, my mother and I went on a three-month holiday to Nigeria, where it became apparent that she had cut off most members of her extended family. In her final years, she only had two close friends from her church. So I stepped in to support her, ill-equipped as I was. We were both fiery, and after an argument she’d clam up. I now wonder whether she felt emotions more intensely and withdrawal was her only way of coping.

All my adult life, my mother had a habit of turning up on my doorstep, unannounced. That would be perfectly reasonable, had she not travelled 6,000 miles from Nigeria. I’m not good with spontaneity, so when I opened the door of my studio flat in 2001 to see her, it was like seeing a ghost. I didn’t realise she’d live with me for a year.

A bonus of her long stay was getting to know each other. She opened up about her childhood in Nigeria. “We grew yams and plantains in the backyard. I loved it.” Her face lit up and I could see the girl in her. Then it went and she’d pray. Intensively. Repeatedly. Something was wrong.

She resumed her nursing career. One day, she showed me an essay she was about to submit for a degree module, and I was shocked: the content was sound, but there was a glaring lack of order. In that moment, I saw the world as my mother saw it: chaotic and terrifying. One feature of autism is difficulty in sequencing information and handling sensory stimuli. No wonder her mantra was, “I just want peace.”

My mother dressed for comfort. She wore white clothes to mimic the colour of her church garments, and the fabric had to be soft and loose around the neck. Often, she’d wear clothes inside out, or the label would be sticking up. But maybe the mistakes were deliberate. Maybe she was hypersensitive to labels and seams, a common feature of autism.

She was definitely sensitive about food and an excellent cook. The year she lived in my flat, I savoured her vegan offerings: fried soya chunks, tofu, moi moi (steamed pudding), breadfruit, plantain. She’d always complained about my cooking, everyone’s cooking. I gladly downed tools and let my mother cook for me – apart from Thursdays.

On Thursday, my mother followed a strict daily routine of prayer and weekly dry fasting (no liquids or food), even when she was ill. Once, a fellow church member encouraged her, “Eat, Sister Helen. You are sick.” In that moment, I realised my mother’s interpretation of her faith was more literal than other church members. My mother adhered to rules, no exceptions.

I told myself to stop being so western and judgmental when she spent so much time and energy praying. The church gave her an instant community and a set of rules to live by. I now see her devotion more clearly. It was deep faith; but it was a special interest, too – autistic people often have an unusually deep interest in a subject or activity. It was the intensity of her prayer, her ability to quote chunks of the Bible, the obsession with the church to the exclusion of everything else, that gave her unbridled joy; and, adversely, an inability to predict the effect of her behaviour on others.

She donated thousands of pounds to the church. My brother and I would end up paying off her debts. She was defensive: “I’m giving money in prayer for you and your brother.” She sent money to Nigeria, so people we didn’t know could pray for us. I was furious: she’d rather give hard cash to the church than emotionally engage with her family. But when I look back, maybe prayer was the way she structured her relationships.

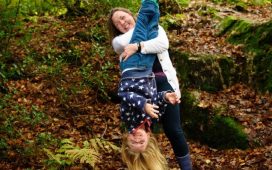

By 2007, I had a second son. Whenever I asked my mother to babysit over the years, her eyes filled with terror. She hadn’t excelled at motherhood first time round, so why would she play grandma? Yet I loved her independence, her refusal to tick the right boxes. Would she have ticked the diagnostic boxes for autism?

When my mother died of a stroke in 2014, I discovered a plastic bag overflowing with unopened packets of medication. She had never changed her diet after she was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. In Nigeria, in the church compound where she collapsed, they told me my mother believed she’d be healed by prayer. Everyone was shocked that a former nurse wouldn’t take life-saving medication. I searched her medical records for clues to her state of mind, but all I found was a question mark around depression.

My mother’s faith both revealed and masked her secret: revealed it through her astonishing intensity and passion; masked it in Nigerian culture, where ostentatious devotion is not unusual. Her stroke might have been prevented had we considered the possibility that her mind was wired differently and been able to get appropriate support. I know the pitfalls of posthumous diagnosis, but I’m convinced my mother was autistic. She wanted relationships but couldn’t maintain them. She wanted peace: she has it now. How many more women are out there struggling, undiagnosed?

It has also made me revisit the question: “Is anyone else in your family autistic?” Maybe. I have traits myself. As a child, I, too, had hyperlexia, a sensitivity to fabrics and a violent aversion to the texture of certain foods. As an adult, I’ve made a career out of my special interest in poetry, reciting my poems from memory without having to learn them. I’ve been self-employed for 30 years, as I work best solo; and all my life have found transitions so difficult that they have triggered depression. But I enjoy parties with good music and ambient lighting. When I took the online Rdos Aspie quiz (designed for adults to find their Asperger syndrome quotient), I scored 113 aspie, 96 neurotypical:“You seem to have both neurodiverse and neurotypical traits.” So who am I? I like the word “neurocreative” which describes how my brain works and what makes me happy.

And what about Solomon? Now 14, he attends a grammar school with support. He loves big, modern trains and Star Wars. He has moderate auditory sensitivities, loves his food and has a broad diet. He is still good at maths and an avid reader. He is writing a novel that features adults with special powers. He’s autistic; he’s neurocreative, too.

● The Infinite, by Patience Agbabi, is published by Canongate at £7.99 on 2 April, To order a copy for £6.71, go to guardianbookshop.com. World Autism Awareness Week starts on 30 March.