Almost as soon as the word Covid is coined, my parents update their “advance decision” documents. They’re constantly adjusting them, fine-tuning their wishes for future medical treatment. “Like a dowager with an elaborate will,” I tease them, blowing the ink dry on yet another signature.

When they first completed their advance decision document, 20 years ago, they were mostly concerned with not being resuscitated should they have a stroke, perhaps while shopping in the market or cycling home. Now, aged 84 and 82 and debilitated by multiple illnesses, they’ve had to give up their bikes and those hopes of a dramatic end. “We look like the old people road sign,” says my mum, bent over her walking aid, handing my dad his stick. And they do. Frail as leaves, they totter down the road to the vegetarian cafe: the wind could blow them away.

These days, all they really want is to avoid hospital. They hope to die at home. To that end, we have bought a hospital bed, a stair lift and adapted the bathroom. But what use is all that in the face of Covid-19, they worry: a disease, they read (for there is nothing sclerotic about their intake of news), that isn’t just lethal to them but would put everyone around them at risk? Who would nurse them if they had Covid?

“Well, me,” I say. “I’ll do it. I’m just round the corner. And, look, I’m breaking the law already, just sitting here.” (For this April is 2020 and support bubbles have not been invented yet.) “I’m not scared,” I lie. “Write it in.” So my parents write their Covid codicils: no hospital, no ventilation. Just painkillers, please.

Maybe they aren’t so unusual. It turns out there is a government drive to get GPs to talk to their vulnerable patients about avoiding heroic interventions in the face of Covid. This drive quite often seems to result in outraged calls to the local radio station, but my parents are pleased when their GP rings. Shortly after, they take delivery of yet another, government-sponsored, advance decision document to fill in. This one is green and a little basic, but it comes with a special pot to keep it in the fridge and the promise that the ambulance man will always look there. My father is so pleased with this detail that he clips a folder of all the previous advance decisions to the fridge door so the paramedic will find them, too. COVID-19 the folder says, in such gothically shaky capitals that after a while my mother can’t bear the sight of it and covers it with a newspaper clipping of Nadia, the Bronx zoo tiger reported to have Covid. “Nadia got better,” she says, looking at the tiger’s dear stripy face. My mother loves cats. My mother loves many things: cooking, the radio, all children, flowers, my father. She is unremittingly hopeful, persistent as spring.

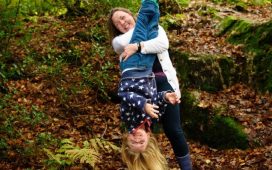

But this spring, I sometimes think my mother is dying. The thought comes to me when she stands among the blooming blackthorn and cannot smell it, when she asks me to taste the salt in the gravy, because that sense has gone, when she suffers painful, sudden, memory lapses only I would notice, and begs me to ignore them. My mother has borne years of debilitating illness and always put her head up, bright and brave, always gone out on the street and found her solace in talking to people. But when I persuade her out in these early days of quarantine, families do elaborate shunning dances around us, pulling their little ones away. One day, a mad person spits on her coat. Another day, a neighbour sprays her with disinfectant, and reminds her to quarantine her shopping. My mother’s head goes down. She says we deserve this because we are breaking the rules when I go out with them. She won’t come to the meadow any more.

When my mother was an excited child on VE night, a jumping jack firework badly burned her leg. Now, as her heart flags and her legs swell and her skin, weakened from decades of steroids, cracks; ulcers and cellulitis appear in the ancient scar. I pack the holes with iodine pads, dry them with honey, take pictures of new ulcers as they appear and send them to the doctor, receive antibiotics by return from the chemist, buy Imodium and probiotics to deal with the harsh side-effects.

My dad watches, worries about his new Parkinson’s diagnosis, the dystonia in his neck, which presses his chin to his chest, his cancer, resurgent again, and always, his depression. Each day we walk the same loop round the meadow and each day he finds it longer. He talks much more than he used to about the past: his school, the brother and sister and cousin he lost when they were young. He talks – and he has never done this before – about his own father, Henry, absent on naval intelligence missions for most of his childhood. He checks I know where the advance decisions are, often, and makes me promise to remove the picture of Nadia the tiger immediately should he or Mum become ill, so the documents will be easier to find.

Amazingly, Nadia stays in place all the way till a morning in late November when my mother, who has another infection in her foot, wakes cold and unable to move. We call the doctor, who calls the ambulance, which comes so swiftly that we barely have time to pack her bags, put her advance decisions in a special folder on top of the radio and Patrick Gale novels, barely time to wrap her in her good dressing gown, comb her hair and tell her she looks beautiful, even now, because she has excellent bones, before the ambulance takes her away.

My mother dreads the hospital for sound reasons. Like hospitals in general, this one is good at heroic interventions, less good at nursing care. It is an academic institution with many groundbreaking researchers, but frail elderly people with tedious, multiple conditions are not often of interest to them. When my mother had an emergency stomach bleed she was superbly treated, but when she had spine pain she was left for four nights on a trolley, and was even trundled to theatre on it at one point to have someone else’s operation (fortunately she was turned back at the door).

Covid restrictions have redoubled this tendency. This time, she is treated with hoo-ha and drastic antibiotics for a suspected bone infection, then with multiple pills for the resultant racing heart, but when scans reveal the infection isn’t there, she is left in a ward for a while before being released without a conclusive diagnosis. Through all this, because of Covid, she has to be alone.

When she comes back home many things have gone missing: the advance decision documents, her digestion, her ability to get to the loo, her steady heartbeat, her confidence, large bits of her memory. She keeps forgetting, for example, that my father has Parkinson’s. She thinks he can bring her trays up the stairs, and he gets stuck trying, halfway up with his head hung on his chest, hands shaking, trapped in his depression, thinking of my mother in bed, bright-eyed and angry, facing off her fear with elaborate plans for lunch. I come and take the tray away and he says he wants to die.

My father sees his death as a boat on a pond. “You’re just out there having a nice time,” he told me when he was first diagnosed with bladder cancer, “getting the hang of the oars, and they call in your number. Come in, number 63. A bit soon, maybe, but that’s all right.” It was soon, then: but that was 12 years ago and that cancer turned out to be containable. It’s back, but my father now neither believes it will kill him nor that it would be too soon if it did. He’s afraid nothing will be allowed to kill him. “The doctors will always think of something,” he says. “They’ll keep pumping you up, making you live.”

In a bid to defend ourselves against the hospital, in an effort to find out where my mother’s advance decision documents might have gone, and if it matters, in a final shot at writing death a really good clear letter (always my parents’ weapon of choice) we ask the GP to come for an end-of-life meeting. Very kindly, since we are now well into the second wave of the pandemic, she attends in person, sits across the sitting room and listens. She, too, is concerned about the fate of the advance decision documents. They must have been lost in the emergency ward, probably early on in the hospital visit because the discharge notes have my mother as “for resuscitation”. The GP says she will sort this out: it’s a serious mistake.

We get out the original documents – there are still plenty of copies – and try to plan for the next time. I’ve heard there are community nurses who come to your home if you are dying, nurses who will give you morphine, put you on a drip, but the GP won’t confirm this. There are some alternatives, the GP says: an elderly unit, a community hospital, but you still have to call the ambulance.

It doesn’t take long. Just after Christmas, we have to call the GP about a new ulcer on my mum’s leg. A paramedic comes to look and raises concerns. He wants my mother’s heart rate measured in a day ward in the hospital. The day ward, he promises, not the emergency unit, but she goes at 11 and hasn’t come back by 4pm, so I call the day ward, and am told she never arrived. I call the switchboard: she was diverted to the emergency unit. So I call and it rings off the hook. I call the number again, and then again. I call it every two minutes until 10pm and only once is it picked up. The nurse tells me she is too busy to let me talk to anyone, there is a pandemic on, but she can see my mother across the ward, alive and on an antibiotic drip. I go to bed.

At 3.30 in the morning, I am woken by a doctor on the phone. He says my mother has developed sepsis and a galloping infection in the ulcer. They are going to operate and she may well die. I am confused, I say that she has advance medical decisions against interventions of this sort. Oh well, says the doctor, we’re working with her, and she’s happy with this. She’s very bright, very alert. And he puts the phone down. I imagine my mother, docile and smiling as she always is in fear. I remember how she agreed to go to the operation that wasn’t hers, was rolled along the corridor, bright and smiling for the doctor. I imagine her infected leg. I imagine her waking up to find it gone. I imagine it is all my fault for not sending her to hospital quickly enough. I get up, and go round to see my father. There is freezing fog that morning, and it is as if I am eating it, as if my insides were full of fog.

My father and I get out the advance decisions again. They are so clear. “In the event of an infection I want to avoid heroic interventions”, “I refuse treatment with a ventilator”, “I do not want my life prolonged if the alternative is permanent nursing care”. But she didn’t have those documents with her, because she was going to the day ward. She had completed full medical attorney documents for me, but I couldn’t be there to advocate for her, because of Covid. And now she has been put on a ventilator, for her operation, and when I call the ICU they say she is stuck on it, she can’t breathe on her own. They don’t know if she will ever come off it, but if she does, they say, she will live a very limited life in a nursing home. “We must hope she dies,” says my dad when I put down the phone. My parents are devout atheists: they believe there is no God and therefore we must live well. So do I. We pray.

Then I start scanning my mother’s documents and emailing them through to the ICU. It seems an especially hard thing to do just then, in January 2021: when the whole country is absorbed in the effort to save the lives of people like my parents, when the national psychodrama is focused on getting an elderly person on to a ventilator, not off it. I’m worried the doctor will think I am a murderer.

But lots of doctors believe in a good death, in fact, and want desperately to give it to their patients. Very many of them are grateful for advance decisions. The doctor in charge of my mother’s care at the ICU is certainly one of them. Over the next two days, we have long conversations about my mother’s steadily failing kidneys and steadily held wish for a peaceful death. She reassures me that she will make no more heroic interventions, that we will be allowed an end-of-life visit. Two days later, she takes my mother off the ventilator so she can die comfortably. My father and I are summoned to the ICU to bid her farewell. My mother lies on a high bed in the quiet of the ward and murmurs “love love” through her mask. It’s unbearably moving and just slightly theatrical and only one thing goes wrong: she doesn’t die.

It’s my brother who finds this out, 24 hours later. He has broken quarantine and driven distances at dawn and begged and pleaded and sneaked himself and my father on to what he thought was the palliative ward only to find my mother breathing with just an oxygen mask, conscious, but off her head. A doctor asks my brother what sort of “cleaning help around the house” is available “when she gets home”. My brother is, understandably, wholly traumatised by all this.

The only hope, we work out, of getting my mother out of hospital and of her seeing any of us again, is to move her and my father into a private nursing home where they can share a quarantined room. My father is willing. The hospital says it is possible. We find a nursing home that can do it. Now we have to tell her. This is hard: the hospital is in full pandemic mode and we are down to one call for information a day, carefully timed to catch a nurse. My brother and I are on a rota – if we both try to call within 24 hours, we will be told off.

I note that one of my feelings, as I beg to know if my mother is still alive, is humiliation, and another is rage, but the dominant one is helplessness so extreme it is leading me to apathy. Versions of these feelings, I vaguely suppose, are the reason there has not been a revolutionary movement across the country to remove older people from isolation in care homes, and also why my father has stopped eating, can’t seem to taste anything and spends most of his time looking at a wall.

On the fifth day, I am called by the hospital. It is a new, senior nurse, asking about an advance decision document. It seems that my mother has been pulling the feeding tube out of her throat and announcing that she has one. Persistently. This nurse thinks this should be listened to. She is so bright, my mum. She has her head up. I love this nurse. I send the documents off again, and the nurse makes a new arrangement: my mother is to be allowed to eat and drink for herself, whatever the risk of choking.

Now the tubes are out, she can speak and hold a telephone. I am allowed to talk to her and am overwhelmed to find she is still there, my beloved mother, still there the strong voice, the eager, empathic affirmation. I tell her about our nursing home plan: we are going to get her out. She will be in a room with my father, soon. She weeps. “I never thought I would be allowed such a thing,” she said. “I thought I had died. I thought you were all dead.”

But of course she is not to be allowed, really. Two days later, she tests positive for Covid-19. She has no particular symptoms, but she must stay in hospital. The day after that, my dad tests positive, too. Most probably he picked it up on the second visit to hospital with my brother. Covid is why he can’t taste anything, can scarcely speak or move, and it turns out I have been strong enough to nurse him after all. I follow all the instructions to quarantine, send away my children and all the help. My father and I sit and look at the wall, alone.

I can’t bring myself to tell my mother the nursing home plan has collapsed. In the one further phone call I have with her I say she is getting out, and she says I am a great woman, a champion. I say soon she will be back in her big chair in the front room and we will be making marmalade, it is the season, and she says that is just what she wants. Then she says good night. I’m not very surprised when the doctor phones early the next day to tell me she has died.

At first my father does not take it in. For three days, he is mostly asleep, and when he is awake, entirely preoccupied with fears about his body: whether he needs the loo, whether he will fall on the step, if he is too cold or too hot. Then his grandchildren come round and stand outside the window, and he is suddenly filled with joy. “I thought I was dead,” he says, just as my mother did. “I never thought such a day would come.”

But with this awakening comes the realisation that my mother is really dead and he has to live without her. He cannot think of a good plan for this at all: the extent to which they had been living for each other is fully exposed. He explains something I had already noticed: that his Parkinson’s means he can’t type any more, and is getting in the way of his reading. There won’t be any more scholarly articles, any more helping young people with their PhDs. His books are all written now.

“Well,” I say, “they’re good books.” When he lies down to sleep he says: “I think about dying, you know, every night. I do want it.”

In the night, his boat is called in. In the morning, I find him collapsed in bed, breathing hoarsely, mostly unconscious. I get out the advance decisions, his and my mother’s, and read them all through. I phone up the doctors and say my father has had a stroke or heart attack and please may I speak to someone.

“You have to call 999,” says the receptionist.

“I’m not going to do that,” I say. “He made an advance decision on that, and it is very clear.”

“You have to call 999 with a stroke,” says the receptionist. “My husband had a stroke last year and that’s what I had to do, call 999. You can’t have any help if you don’t call 999.”

“OK,” I say, “we won’t have any help. Please will you inform the doctors?”

And that turned out to be the right thing to say. With that last, desperate, refusal, my father and I pass through the looking-glass into the world of those dying at home. We are amazed and grateful to find that even in January 2021 the GP will come to the house, district nurses will call twice a day and fit him with a driver for morphine and a fantastic new anti-anxiety drug, the first, perhaps, to touch his problem. “I am so impressed with this letting me die business,” he says to the nurse, in one of the last times he fully opened his eyes.

“Pace yourself,” all these visitors say to me, though it is not clear how I should do this. The council phones to tell me that I am entitled to carer support, but as there aren’t any carers, I won’t be getting any. But when it all gets too gruelling, my brother appears, my cousin, my niece and nephew, my children, and we manage. My father rallies to listen to messages and say goodbye to us, then struggles, then sleeps, then, after 10 days, dies. The primary cause of death is certified as takotsubo cardiomyopathy, or a broken heart. Covid-19, as it is for my mother, is listed as a secondary cause.

And thus both my parents become statistics on the news. They are in so many ways typical Covid victims – exactly the median age with a number of co-morbidities – that I feel I should be able to find them in those numbers, mourn them when the nation stands in silence and puts out flags for the fallen. It’s hard, though. My parents weren’t fighting that war. If Covid shortened their lives, it was not by much: the loneliness of lockdown hit them harder. They did not want to combat death: they were trying to let it in, to find a human way to go. It was extraordinary and revealing of the values of the NHS that in the middle of a pandemic, their hospital did not hesitate to give a hi-tech emergency operation and three days on a ventilator to someone as frail as my mother, but also indicative of our norms around death that no one stopped to ask if she had an advance decision in place.

But our family isn’t “ripped apart” by their deaths, as the current narrative would have it either – certainly not as it was by the premature deaths of my father’s siblings. Four generations and three removals of cousins came together to talk about my parents and trace their long paths in our lives. Friends, colleagues, students, lodgers from three towns and 60 years of writing and teaching have got in touch. We want a funeral, desperately, but we plan a party for the summer instead and turn to letters and social media. In our talk, I find my parents warmly restored to me, not as the old people sign, but as themselves, as Joan and Michael Clanchy, headteacher and historian, grandparents, aunt, uncle, cousins, friends: gifted, giving people, widely known and deeply loved. My mother and my father, who loved me and each other, who lived long, rich, lucky lives, and who died timely deaths at the end of them.