We talk a lot about Down syndrome in our house. My youngest child Greta, now 5, was diagnosed with mosaic Down syndrome just before her second birthday. My partner and I have fielded many questions from her older brothers Jasper, 10, and Rory, 8. Early on, when we were learning key word sign to help Greta communicate, they asked, “Will she be able to talk?” I explained that her vocabulary would likely grow and that if it didn’t, we would find other ways to make sure she could let us know what she wanted and how she felt.

Now Greta is doing the asking. At bedtime a few weeks ago came the question, “What does Down syndrome mean?”

“It means you have an extra ingredient,” I replied. “Not many other people have that ingredient. It means you’re amazing.” She proudly shimmied her shoulders and snuggled into bed.

But in the days following her diagnosis, I would never have used the words “Down syndrome” and “amazing” in the same sentence. Despite my little girl’s happiness and good health, and despite the joy she brought to our family, I was sure that confirmation of her extra chromosomes would irrevocably change her life – and our lives – for the worst. I had much to learn and even more to unlearn.

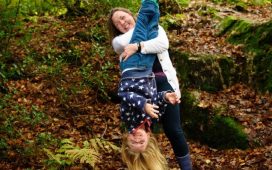

Over the past few years people with Down syndrome and their families have provided me with an incredible education. As has Greta herself. I’m no longer surprised by her tenacity, her willingness to persist at learning things that might come easier to others. Around the time of her second birthday, we were using laminated photos of Vegemite and peanut butter so she could easily point to what she wanted on her toast. Months later when she said her first two-word sentence “more strawberries”, I gleefully messaged all the family before heading straight to the supermarket for more supplies.

A few years on I couldn’t have imagined the conversation I recently overheard between Rory and his friend. “Does your sister ever stop talking?” his friend asked. Rory replied: “When she’s asleep.”

Thinking back to my fear at the time of Greta’s diagnosis, I wonder what it would have been like to learn of her genetic makeup while I was pregnant.

There are around 400,000 pregnancies in Australia each year and a growing number of would-be parents are choosing noninvasive prenatal screening (NIPT). NIPT marketing material tends to focus on the “relief” and “reassurance” that a low-chance screening result provides. But I’ve been struck by the silence surrounding the 2-3% of NIPT results showing a high chance of a chromosomal difference.

In my role as host of a new podcast called One Screened Every Minute, I’ve interviewed people who have received high-chance NIPT results for a range of chromosomal differences, including Down syndrome. These stories are shared so we can learn but not judge.

The interviews reveal the immense emotional toil required to understand and navigate decision-making about proceeding with invasive diagnostic tests and ultimately whether to continue or to terminate a wanted pregnancy. While scientific advances arm would-be parents with an accurate chromosome count, what this actually means for their future child is far less clear. In the search for answers this void can be filled with fear and misinformation.

In the recent ABC documentary, The Upside, obstetrician Professor Steve Robson was interviewed by Julia Hales. He said that a huge issue for doctors is the fear of “missing” a diagnosis of Down syndrome, and of being sued. When Hales asked Robson, “What do doctors know about life with Down syndrome?” he readily admitted: “A lot of doctors these days don’t have a lot of experience [with Down syndrome] and in many ways they almost fall back on textbook descriptions.”

A clinical environment in which doctors know little about life with Down syndrome – and fear litigation – is not conducive to informed decision-making. But when prospective parents are deciding whether to end or continue a wanted pregnancy, they need balanced and accurate information. Could the stakes be any higher?

On the podcast, Dr Melody Menezes, head genetic counsellor and scientific director at Monash Ultrasound for Women, suggested that concerns about potential litigation are blinkered. “I always am worried that . . . someone could . . . interact with someone with Down syndrome at work or in the community and go back to a health professional and say, ‘You didn’t tell me that that’s what my child could have achieved. You didn’t tell me that that’s what this could have been like for them.’”

There are risks in leaving out the good stuff – what is often referred to by those in the know as the “extraordinary ordinariness” of life with Down syndrome. Menezes refers prospective parents to Down Syndrome Victoria for the opportunity to hear from people with Down syndrome and their families first-hand.

An application to have the cost of NIPT subsidised through its inclusion on the Medicare Benefits Schedule was rejected in late 2019. Those supporting this move argue it is necessary to allow equity of access to screening technology. Whether NIPT is subsidised or not, the ethical use of this technology relies on prospective parents receiving accurate and balanced information, together with the time that they need to make informed decisions, both pre and post screening.

Surely this is the very least you should expect when you’re expecting.

-

Elizabeth Callinan is host and executive producer of One Screened Every Minute. The podcast is produced by Joel Supple and supported by the University of Melbourne, Melbourne Disability Institute and the Vasudhara Foundation.

-

The Upside is available now on ABC iView.