For quite a lot of my late-adolescent and early-adult life, I thought that a positive pregnancy test when you want a baby might be tender and even romantic. “You’ve got to be kidding, Clover.” Pete’s face slides downwards when I stand in front of him in our room, holding out the test box.

A rare moment: the house is still and we’re alone. I am as apprehensive as he is. Having another baby will be like letting a wild animal into our life. Although I want the mess, the reality is terrifying. I really want this baby. I must have it. But it will also take up so much of my brain and my life, that however much I want it, I know another child will stop me having the thoughts I want to have, and, to a great extent, living the life I want to lead.

I know, too, that motherhood can bring a sort of violent, overwhelming love that feels like being encased in metal and dropped into a deep sea.

“Oh God, oh God, oh my God!” Pete says when I show him the two lines. “I mean, it’s amazing, incredible.”

He buries his head in his hands. Then he laughs.

“What a nightmare! An amazing nightmare!”

He reaches out to me, enclosing me in his arms, the safest place in the world I know – because he’s so up for life, he’s never scared. “Five! Five children! What the fuck is that going to be like?”

***

I was 34 when I met Pete. Jimmy and Dolly were nine and six and we were close in a special way; I had split up with their father after Dolly was born and while Jimmy was still almost a toddler. Most nights, the three of us tangled together to sleep; absolute single motherhood was financially terrifying but filled my heart and head with complete love.

When Pete and I fell in love, my family shifted, and resettled. Pete’s heart is huge, his love absolute, and he wrapped it around the children as much as me.

My band of three became our band of four and then five, when Evangeline arrived in 2012, and, soon after, six, when Dash was born. Life got messier, noisier, funnier. But the new, big family also brought newer, bigger responsibilities. We spilled out of the house Jimmy, Dolly and I had been living in when I met Pete, into the countryside, where there was space for us all. But the move also made life more complicated. Pete spent more time away, working to support these children he adored. Most of the week, we were often living apart. And I was the parent the children turned to for help, since I was always there.

When I have the space to think of Pete, I miss him, because there are so many of us in this marriage. When he is at home, it’s almost impossible to have a conversation, interrupted incessantly by children swinging from his arms like comedy bananas. The children chatter away to him all the time and I am pushed aside like a silenced scullery maid whose role is to wipe surfaces, find shoes and carry coats.

I miss the people we were, before we became carers. I’m never ashamed of who I am in front of him, even when I’m angry and hateful with exhaustion, and I crave more of him. Sex is the place we can find one another again.

Sex is also the opposite of motherhood. As a mother I have to pretend to be the person I really am not: patient, hygienic, gentle, good at craft, moderate, rarely anxious, never depressed. When I have sex I can forget all that control and be something different, unembarrassed and lustful, like an animal, but also absolutely human in a dark and disgusting way. It’s easier than anything else I know how to do.

Apart from sex, almost everything we do together is about us as a mother and a father. Sometimes I think I must become someone else through sex so I don’t feel as though I am betraying my children. Sex necessarily involves shutting them out of my mind and my space.

One of the best things I have done to improve the sex we have, far beyond vibrators and paddles and underwear or even that harness that ties me up, is to put a lock on the inside of our bedroom door. It frees us from cowering under the duvet listening out for small feet.

Sex enables me to become the woman who doesn’t worry about whether everyone has their coats for school or homework has been done. I can’t really do anything about the kids when my wrists are pinned to the bed and my face is forced into a pillow. Sex like that takes you to different places, like suddenly being on very strong drugs. After, there is the unfamiliar, wet reassurance of spunk on the sheets. Something fragmented in me feels, for a moment, as if it’s put back together.

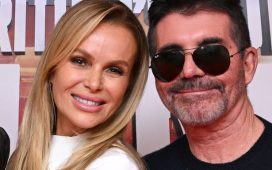

Those two blue lines turned into a pregnancy and then a birth as Lester arrived, shining and perfect in our lives. Babies being love, but separation, too. By the time Lester, is eight months old, Pete and I are in danger of seeing one another only as caregivers, of failing to even see one another at all. We need to go away – just the two of us – before we vanish from one another’s sight.

At the airport, carrying my one piece of hand luggage, I see a look of gentle despair cross the face of a woman as she wakes her sleeping baby, who starts crying, in order to fold the buggy to pass through security. She calls her husband to help, but he’s wrestling with their son, holding his tiny wrists as he strains and screams to run back out towards the entrance. The child kicks him and the man’s face creases. I feel I ought to ask the woman if she wants help, but I can’t stop and offer a hand to every woman in this airport with a screaming child.

We sit for 20 minutes in a cafe, waiting for our gate to be called. Just being alone with Pete, drinking coffee and nothing else, is a deep pleasure. We laugh at each other’s jokes, speak in whole sentences and start and finish a conversation. I want to touch his face, to reacquaint myself with all of him again. More than anything, I want to remember how it feels to love him, and to really see him. Absolved from being a mother, I am someone different: less harassed and calmer.

In my 20s, I lived on a Texas ranch and knew a cowboy called Powder who was deeply loved by his wife, Janey. They had small children, but whenever I passed them on the dirt track that led to their cabin, Janey would be sitting right next to Powder on the bench seat in the front of his pickup. When I remarked on this to another cowboy, he nodded and laughed. “Even with all those kids, Janey sure does like to sit real close up beside Powder.”

I wanted to be like Janey – to meet a cowboy I wanted to sit right up close to in the seat.

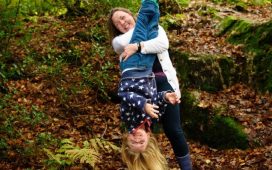

Sometimes there are days when I think cuddling Evangeline as she falls asleep, or snuggling up to Lester and Dash as I read to them in bed, their pyjama-covered limbs tangled around mine, is all I need. There are times when my skin is pressed up against that of my children and we’re breathing the same air, all hot and close like we’re still one person, when I feel that I love cuddling my young children more than I love sex. But now, being alone in a hotel room with Pete, I feel an almost hysterical lightness. There is an acute novelty in not being needed for caring, instead doing something purely for pleasure.

There’s the novelty of reaching across the empty space between us, and realising that the person we find there is still the one we love most. And the novelty of sex in the afternoon and sex in the morning because no one else is in bed with us.

When it is just us, I become someone different. I become the person motherhood separates me from. It’s like waking up. It’s exciting, and consoling, too, this feeling that we are still there for one another. That we have not lost each other. That we have not lost us.

How to keep the intimacy

Snatch moments alone together Pete and I spend a lot of time apart, exacerbated by the fact that he works abroad, too. Sometimes, weeks, even months, will pass when the best we can manage is a late-night trip to the supermarket. Yet even a 10.20pm drive to the Co-op can be enough to remind you that you are two people who loved one another before children arrived.

Ease up on social media I spend a lot of time on Instagram, not just because I’m addicted to it, but because it’s essential for work. But we make an effort to put away screens during our time together. At least, get an alarm clock and take phones out of the bedroom.

Don’t hold on to a grievance In a long-term relationship, little hurts will stack up and fester into something toxic. Even when we fight, which happens a lot, I try to keep part of my mind open to the fact that we want, ultimately, to remain married. Vicious words may be said in the heat of a row but putting it away and turning back to face one another as quickly as possible matters to the survival of your relationship. Do not fight to win an argument, as all you are doing is proving the other person is an idiot, which makes you the idiot for having married them in the first place.

Fix a lock on the inside of your bedroom door I’d like to say this is so you have all the sex you want without being disturbed, but it’s equally important to be able to finish those conversations about whose job it is to tax the car or find a new mortgage broker uninterrupted by demands for clean PE kits or a missing cuddly toy.

Have sex, with each other, as often as possible When you’ve had sex, don’t allow yourself not to bother again for another month, but have sex again the next day, too.

● Extracted from My Wild And Sleepless Nights: A Mother’s Story, by Clover Stroud, published by Transworld on 20 February at £14.99. To order a copy for £13.19, go to guardianbookshop.com.

If you would like your comment on this piece to be considered for Weekend magazine’s letters page, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).