![]()

Emotional Intelligence (EI) is the capability of individuals to recognize their own, and other people’s, emotions, to discern between different feelings and label them appropriately, to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior, and to manage and/or adjust emotions to adapt environments or achieve one’s goal(s).

When dealing with people, remember you are not dealing with creatures of logic, but with creatures of emotion. —Dale Carnegie

The concept of EI has been around for decades, and much has been written on the topic, most notably in Daniel Goleman’s book, Emotional Intelligence. Studies show that people with a high EI can be more successful, as well as happier, in life than people with a high IQ (the total score from several standardized intelligent tests.)

Some of the goals of psychotherapy are to be “happier,” more content, and to have a better understanding of our feelings and ourselves. That can also be said, I propose, for photo therapy. What photographer wouldn’t like to be more confident about their work, feel more fulfilled, and better understand what and why they photograph certain subjects?

Nota bene: I put “happier” in quotes because happiness is relative. What’s more, in psychotherapy the opposite of “happiness” often happens: one experiences and learns how to bear pain.

In photography, we can feel (and can illustrate within a frame) pain, too. Just think about some of the topics. Think about how a still photograph can have a sad or painful effect on you and others. The 1972 Vietnam War black-and-white photograph, Napalm Girl, which shows a 9-year-old girl, crying, burning, and running naked from the fire comes to mind.

Taken by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut, it is the single photograph that helped to end the war, in which more than 58,000 American soldiers—and more than two million civilians on both sides—lost their lives.

FYI: Now a woman, the subject in the photograph, Kim Phuc, lives in Canada. Several years ago, she was awarded the Dresden Prize for her peace work.

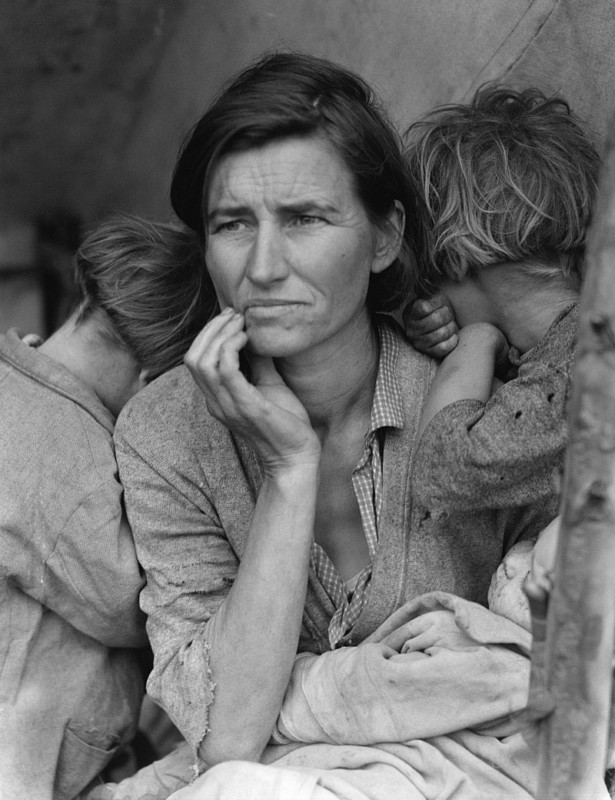

Another equally well-known (among avid photographers) and emotionally stirring photograph is Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother. The black-and-white photograph, taken in 1936 in Nipomo, California, during the Dust Bowl era, shows a 32-year-old destitute pea picker, Florence Owens Thompson, mother of seven children, with an aged face that is filled with despair.

Of course, you can think of countless still photographs that made you smile and laugh and feel great, too, such as photographs of your loved ones, wildlife photographs that show big cats at play, and spectacular sunrises and sunsets that are nothing less than awe-inspiring and give us the “great to be alive” feeling.

One such photograph comes to mind. It’s the famous photograph taken by Life magazine’s Alfred Eisenstaedt (1898–1995) of a sailor kissing a passing woman in Times Square in New York City. It was taken on August 14, 1945. The sailor was celebrating the United States’ victory over Japan.

You might want to do a Google search on the photography legacy of Alfred Eisenstaedt, whose nickname was “Eisie.” I had the honor of interviewing him in 1978 when I was the editor of Studio Photography magazine. He, like most of the professional photographers of that time, was interested in the art and craft and power of photography, unlike today where some photographers are more interested in the number of followers they have on social media than in photography.

Okay, I know I digressed, but I wanted to reinforce the power and meaning of a still photograph, the photographs that you take. Now, let’s get back specifically to the subject of emotional intelligence for photographers.

Just as we can improve our photography, we can improve our emotional intelligence, which I feel is important to being a photographer. Basically, we need to be more aware, or as my friend Hal Schmitt, a former Navy fighter pilot and Top Gun instructor puts it, we need to have “situational awareness.”

When it comes to being a photographer, emotional intelligence is the key to being aware of the feelings of the people you are photographing, the people with whom you are working, and your effect on others.

Knowing one’s effect on others is key. The opposite of being aware is being numb, and I am sure you know or have met people who are numb.

Here are two examples of people being numb:

#1.

Susan and I happened upon a sacred outdoor Buddhist ceremony in Sri Lanka. A novice monk was leading dozens of practitioners, who were sitting respectively in front of three carvings of Buddha in the side of a stone mountain, in a hypnotic chant. It was a wonderful sight and sound experience. Shortly after the ceremony started, two women with cell phones (and loud dresses) stood up and walked around taking photographs. It was disturbing, to say the least. In a word: obnoxious.

#2.

One afternoon, Susan and I were in Zion National Park in Utah, photographing the amazing landscapes. At one location, six tourists from another country jumped a fence behind which we and several other photographers were standing—because a sign said: “Please stay behind this sign.” The tourists walked into the prettiest part of the scene and proceeded to take selfies, while making silly gestures, I might add. Of course, they were wearing loud red, yellow, and green windbreakers and jumpsuits. In a word: numb.

So here is the good news about emotional intelligence: the side effect of having emotional intelligence will be that you’ll be happier — or perhaps more joyful is a better term — doing what you like to do.

Here are a few examples of how emotional intelligence can work for photographers:

Respect the Subject: When photographing a person, every movement and gesture we make is important, so we need to be aware of our body language. Moving quickly can be interpreted as being aggressive. Move slowly and you will be less intimidating. Waving your arms around with a big gesture can also intimidate a subject, while slight, gentle movements are more accepting.

We need to be aware of what we say, even if it is through a guide. We need to be aware of the tone of our voice. I try to speak extra gently when I am photographing a stranger in a strange land.

I also speak softly when I am photographing someone in my home studio. I am very aware of my tone, and how my subject could perceive it.

We even need to be aware that the clothes and shoes and jewelry, including a watch, we wear can have an effect on the subject. Wearing a flashy watch in a Hindu or Buddhist temple says, “this person is rich” to a subject, who may not be rich and who is not into material objects. That disconnect with values could mean a disconnection with a good photograph.

Space: A photographer also needs to be very aware (again, have situational awareness), emotionally aware, of space—the distance between the subject and the photographer.

It’s true, the closer you are to a subject, the more intimate the picture becomes; however, if you move in too close, you can intimidate a subject. When in doubt, ask if you can get closer. Sharing your pictures on your camera’s LCD monitor or smartphone gives you a good reason to get close to your subject, which might bring you “closer” to your subject.

Time: Photographers also need to be aware of the time they spend with a subject. We need to work fast, and to be aware of not overstaying our welcome. The best way of working fast is to know your camera, so you can make fast adjustments. The best way to master your camera is by practicing, every day.

![]()

Editor’s note: This article is a condensed version of Chapter 7 in photographer Rick Sammon’s new self-published book Photo Therapy — Motivation and Wisdom: Discovering the Power of Pictures (available in both Kindle and paperback forms). The 178-page book contains 0 photos and 35,000 words, and it’s designed to make you think hard about your photography in order to become a better photographer. As Ansel Adams once said: “The single most important component of a camera is the twelve inches behind it.”

About the author: Rick Sammon is a Canon Explorer of Light, book author, Photoshop guy, workshop instructor, musician (keyboards/guitar), and proud dad. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of his work on his website, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Image credits: Header photo by Rollstein