This article contains full spoilers for this week’s episode of The Deuce.

When David Simon describes an actor’s performance as “one of the best I ever got on a show,” the compliment demands attention. From The Wire all the way through The Deuce, Simon has helped to make stars out of unknowns (Idris Elba, Michael B. Jordan), has gotten remarkable work from established names (Oscar Isaac, Maggie Gyllenhaal), and has assembled a brilliant repertory company of character actors (Wendell Pierce, Khandi Alexander, Clarke Peters). Simon saying this about Emily Meade’s work as prostitute-turned-porn-star Lori Madison on The Deuce is no hollow bit of praise.

It’s also not surprising to anyone who’s been watching Meade’s work across these three seasons of The Deuce, including this week’s penultimate episode of the series. In it, a broke, despondent Lori returns to New York, ponders relaunching her porn career, and instead turns one last trick on 42nd Street before blowing her brains out with a revolver she’d purchased a few episodes back. Meade’s performance was, as it had been throughout the series — particularly in scenes opposite Gary Carr playing Lori’s former pimp, CC — raw, committed, and charismatic, even in such a sad and empty moment as the final one. She’s not the most famous person to appear in the series, but her work might linger the longest with those who watched it all.

As Simon explained, sitting alongside Meade during a conversation at HBO’s offices last week, “She created this arc that we’re incredibly proud of. It basically has to deliver the cost of all the themes that we’re dealing with. The character is the cost personified.”

Was Lori’s arc the one you had in mind when the show began?

Simon: [Emily and I] talked, and I sold hard tragedy. I had this vague meeting with all the actors who were going to be engaged in the porn world. I knew there were all these sexually commodified scenes. I was basically trying to talk them in or out. I wound up talking out a couple people, actually. But I said to Emily, “You read really well. We’ll work together, if not on this then on something else.” I think I used the word “tragic,” right?

Meade: You actually gave me the option between two different characters. And one had a happy ending and one had a tragic ending. I automatically, instinctively leaned towards the tragic ending. I asked, “Which do you think will have the greater impact?” And we both agreed it would be the tragedy.

So you were not in any way scared off by what David was telling you?

Meade: I wasn’t. Maybe I wasn’t fully thinking. [Laughs.] I was probably being insensitive to myself. There’s almost this athleticism that comes out in actors when someone says, “This will be difficult,” and you go, “Oh, what do you mean? Life is hard. I’ve dealt with it!”

Simon: That’s really true of actors. “Can you ride a horse?” And they say they can, even though they never have. It wasn’t just the hyperbolically sexual role. It was also the emotional track: 24 or 25 hours of television that were going to go to a very dark place.

Did you know specifically where the character was headed?

Simon: George and I knew where we were going. Even before Season Three, I was talking about the means of suicide. Should it be quiet? Should it be loud? Even though you’re talking about the darkest possible stuff, you’re trailing the arc behind you and can see what you’ve built. Now it’s about nailing the last boards in and putting the paint on. So that’s always fun. The last few episodes, it feels like you’re paying out. You’ve been husbanding stuff and putting it in the bank, and now you’re on a spending spree.

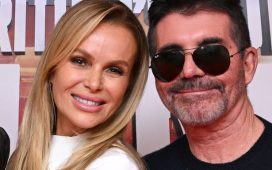

Gary Carr and Emily Meade. Photo by Paul Schiraldi/HBO

Knowing her story would not end happily, Emily, how did you choose to play Lori out of the gate?

Meade: What made Lori interesting in the pilot, before you get to the other episodes, is that she was presenting herself in a false way at first. I think I was preemptively trying to find the layers that I was assuming would exist. How I see it, Lori comes off the bus and she’s pretending to be more innocent than she really is — but in truth, she really is more innocent than she thinks she is, and she’s getting herself into more trouble than she realizes. It’s endless layers.

Simon: You know there’s a tragedy coming, that there’s something not right here — there’s some hole in this character that she never quite gets to fill. But you also know that she’s streetwise. This world is not alien to her. That’s a lot to play. So when you go back and look at those early moments, it’s all there. The Lori that is ultimately going to get crushed is in there, but also the Lori who can go on for years and years.

But also, sometimes we’re in the writers room, and we’re trying to say [political] things with characters, and you can often get lost on the fact that the character has to occupy space that the character understands. All the didacticism of, “Oh, we want to say this about sex work, we want to say this about misogyny, we want to say this about control,” great. But on some level, Lori has to be explained to Lori. And there was a moment sometime in first season where [Emily] said, “She just really wants to be loved.” And that cracked it. It was a bunch of writers sitting around with big schematics on the board, and we go, “Oh, yeah. That, too. Shit.” At that point, I knew we were never going to explain where the hole came from, but I wanted that scene in Minnesota and Lori looking at the house. That was in the idea you gave us about her wanting to be loved. Something was unattended to at a very early moment in Lori’s life. And we worked back from that premise.

The final scene between Lori and Candy underlines the mysteries of her backstory: No one on the show or in the audience knows anything about her. So how do you as an actor build up in your head who she was before she got off the bus and met CC?

Meade: In the beginning, I was nervous and wrote some kind of biography, tried to figure out her astrological sign, where she was from. But things [in the show] would shift, and as it went on, I was always able to connect to the baseline that she wanted to be loved, and she only knew how to find that through sexuality. Which is a really relatable thing to all humans, but especially to humans who are trying to be famous. So it’s a way to connect that to the job that we are all doing. That was always there, and as the time went on, everything fell into place with what I innately felt. I never stuck to one specific storyline of her past. I’m assuming she has some kind of daddy issues, some kind of sexual trauma. That’s very basic things. But it didn’t matter specifically. When I looked at that house, I saw that, yeah, she was abandoned and she didn’t have her needs met. Whatever format that was in, those were the main pieces of the puzzle.

Photo by Paul Schiraldi/HBO

David, was one of the reasons you didn’t want to give her a backstory that she has to symbolize the cost of the business?

Simon: Lori’s backstory needed to encompass all the backstories, in a way. We just revealed Candy’s story. But Candy is, in some weird Candida Royalle auteur way, not indicative of the larger diaspora of sex work. So we could risk it with that character. The more interesting thing with Lori was, by virtue of remaining tacit on it, it incorporates a lot. In some ways, we never had a discussion about it, but I remember writing that line in the pilot [about daddy issues]: “Don’t we all?” Something happened, it happened young, not necessarily sexual abuse, but it could be neglect. It only mattered that Emily internalize it in a way that could drive the character. There were moments, even in the pilot, when we got ecstatic. We were watching the dailies of the bedroom scene with CC where you’re reading the magazine article about Jane Fonda in Klute, saying, “I could do that.” The attention to fame and celebrity was important. It’s elemental to the rise of porn. That was delivered. The less said sometimes, the better. When it’s on track, shut up. Don’t graft on, “Well, in junior high, this also happened.”

How do you think her suicide is going to be received?

Meade: It’s going to be interesting to see the feedback with Lori. On social media, I see that people so badly want her to be OK! As much as it’s going to be so sad, she needs to not be OK.

Simon: To stand for something.

Meade: Not to send some moral lesson, but it’s not easy to be OK. It’s so important. So I’m glad I chose the tragic. As much as people may be angry.

Simon: [The suicide is] a disturbing sequence. I’ve now seen it 30 times, and every time, there’s literally a part of [me] going, “Don’t do it! I know the last 29 times, you reached into your purse, but maybe this time…” You still wince at it.

Meade: I even felt that. At first, I was much harsher on Lori. I was adamant that she wasn’t just a victim of others — she was a victim of her own ego and self. But by the end, I really did gain so much empathy for her. I went on the journey with everyone else, and I started going, “Maybe she won’t die!”

David, when you say it’s the most disturbing sequence… you’ve killed children on your shows. Oscar Isaac shot himself in a cemetery in one of them. What was it about this one that made your reaction so visceral?

Simon: First of all, the way [Emily] acted it. The definitive moment of doing it quickly. Suicide is a disturbing act. It’s often something that infuriates viewers, and rightly so. Not only do they come to embrace a character, but the idea of anybody nullifying themselves when the viewer sees all the human potentialities is infuriating. Some viewers don’t want to accept it on any terms. I know this. I watched it with John Goodman’s character in Tremé. All the signposts of where he was going were there, but people still don’t want to understand it. All the placemarks for Lori were the same way. But there was something about how it was played.

[To Emily:] You saw the anger, and you saw the nullification and self-loathing. It was so deliberate, how you did it. That made it more disturbing. You leached all the melodrama out of it. Melodrama around it is inevitable anyway. It doesn’t need more. There was no soliloquy on your face — it all happened well before the moment of the gun. The wide shot of you when you’re out on the street, and you’re about to pick up the last trick, there’s more of a soliloquy on your face there. Which I thought was brilliant acting.

Emily, what do you remember of filming that last scene?

Meade: Obviously, it was a very important scene. Actors put a lot of pressure on themselves. But it felt kind of easy and simple. Everyone on the day was going, “Oh, this is a sad day!” People were crying. I kind of felt nothing? But I pretty quickly embraced that through the day, because that’s how I think Lori would have felt. Thank you for saying it was performance, David, but it’s also in the writing. She’s already decided before she pulls the gun out.

When do you think she chose?

Meade: Everyone was debating that on set. I think it’s something she had thought about for a while. It has to have entered her head. I don’t know if I can even commit to a moment where she definitely thought it, but it was something that was constantly lingering in that journey. But in that episode, she goes down that checklist, seeking comfort anywhere she can from whoever she can. I think there are multiple layers to her deciding in her subconscious. So on one level, maybe she knows where she’s headed, but it’s not until she checks it all off — Turning a trick doesn’t do it anymore; doing coke doesn’t do it anymore — that she settles on, “There’s nothing in this world for me anymore.” Which is devastating.

Photo by Paul Schiraldi/HBO

Simon: I also felt that if it hadn’t been so fast and so deliberate, she might have stopped. It was almost a willful, “I am not going to stop myself.”

Meade: Sadly, it’s part of the stubbornness she’s always had. The beginning of this season is her trying to find ways to not do it. Can I leave porn? Can I do this? But it’s always leading here. I’ve always thought her ego was the death of her, ultimately, so there is this stubborn part of her that doesn’t want to work hard and isn’t willing to live in that pain. So there is an immaturity and stubbornness to it still.

There’s the bit of business with the cocaine right before. Why do you think she doesn’t do it?

Meade: I think it’s just a “Fuck it, there’s no point.” Maybe she doesn’t want that to stop her. She doesn’t even want to feel good for a moment and maybe question it.

As important as it was to portray the cost of sex work through what happens to Lori, the show also portrays Candy and occasionally some other people benefiting from their involvement in porn. As you were making the series, how conscious were you of this balance between illustrating the good of porn and the many bad sides of porn?

Simon: Or at least the variety of outcomes. Early on, while I was researching it, I went to Candida Royalle’s memorial service, which happened to occur simultaneously to us getting ready to film the first season. And I met a lot of veterans from the early days of pornography. And one of them, Jane Hamilton, whose screen name was Veronica Hart, said something that pulled me up. I was well aware of the rate of attrition in pornography. It’s like the NFL: Careers are short, everyone ages out, there’s a lot of burnout. It’s what you would think from something where the laborer is the actual product. So I started to say something along those lines, and Jane gave me a great gift. She said, “Do not make it so that everyone is a victim. For some of us, this defined us in ways that worked. Some people could handle it, some couldn’t. Some seized on moments that they’re glad they had, and some wish that they’d never walked in the door. If you don’t include the other ones, then you’re lying.” I remember thinking, “We have to array these characters so that some stay in, some get out, some struggle, some are exalted.” And that was important.

What sort of feedback have you gotten from people currently working in the industry?

Simon: There are people in the industry who very much identify with characters in the show, and Lori in particular. And I think there’s going to be a little bit of heartbreak. They want to see a better outcome, because they’re vested in a better outcome in the most basic ways. We’ve had consultants all the way through, but we picked up some fresh consultants for this season, because getting into porn in the Eighties was different than in the Seventies. And it was a fresh set of eyes telling us, “You’re OK.” That was reassuring. You just want to get the details right so you’re laying yourselves out. But they’re very vested in Lori. I may have to stay off Twitter for a while.

And on some level, we can only imply where porn went, beyond the mid-Eighties. Some of the forces that were going to transform porn were already on the table back then, but they hadn’t run their course. Porn was already on the way back to being solely for the male gaze and male gratification. All the pretense of, “Oh, it’s going to have fucking, but there’s going to be story in it,” that was gone. Once it didn’t have to have a theatrical release, it became really reductive. So if I had to guess, if you got into porn after the time of The Deuce, it was always on those terms. Whatever we’re saying about how porn took a darker turn, I think if you’re a performer nowadays, it doesn’t even seem darker or tougher to you. It just is. More misogynistic and more specific to various fetishes. If you got into porn after 2000, the angst of the pioneers is not necessarily your angst.

Over the first two seasons, there are a lot of tough scenes between Lori and CC. Emily, how was it for you and Gary to have to play that material together? Especially something like that final scene together where he rapes Lori?

Meade: I know it’s a disappointing answer, but it was really easy with him. He’s truly one of my best friends, and one of the most magical, kind, not-human humans I’ve ever met. Since we were there together from the pilot, and it was a very challenging world to enter together, we were bonded over that. There was never much discussion or decision-making over our dynamic. Maybe it was our light sides meeting in person and our dark sides meeting on camera. But it was very intuitive. We didn’t have to really discuss it. Because there was so much trust and kindness between us in the light of day, it always felt very safe. In that last scene that we had, which on paper should be a very difficult scene — it’s sexually difficult, it’s violent, it’s sad — but between takes, we were giggling, and there was this weird levity. As soon as we wrapped that scene and I realized it was our last one together, then I started hysterically crying. I think everyone expected me to be a mess during that scene, but having to say goodbye to him was the hard part.

Simon: Lori’s character, there were also these moments of delivered sarcasm or toughness that are genuine, that are some of my favorite lines in the piece. You didn’t make the character cracking or melodramatic at every moment. That moment on the porn set where you go, “I’m gonna finish my cigarette,” that was like out of a noir. That was what an actress like Barbara Stanwyck would do. That was the other thing you’re relying on when you cast someone like Emily. If you saw them overwhelmed by what they had to endure, it would be too much. The fact that it was masked for 25 episodes was important. You had to be tough.

Photo by Paul Schiraldi/HBO

Meade: Yeah, she’s not feeling what we as the audience are feeling as we’re watching her. Same with the relationship with CC. Gary and I were always defensive of our relationship. People saw him as this evil pimp to my prostitute, but we were like, “What do you mean? CC and Lori are in love.” Also, there was a lot of humor to that, because where they connected was that they were both eager to prove something. They were both these little hustlers constantly trying to one-up each other. So once Lori left CC, she’s not experiencing the pain, even as it’s painful to watch her.

Simon: Then there’s that moment in the diner where Frankie informs you that CC is dead. I told you we were going to just let the camera run. And you go from genuine grief to, “I’m free.” And we watch you change in real time. There, we got to the point of, “OK, we have 58 minutes and 30 seconds. After we cram in everything else that we need, how many seconds can we free up for Lori at that table?” The more you let it out, the more it just sold. It was so great.

One of the more striking Lori scenes this season was when she came back to New York and danced with Vincent. How did you feel about that?

Meade: It was another of Lori’s attempts to be a real person, to be a human. She knows Abby, and she knows Vincent’s life, so to her, him being attracted to her in that moment makes her feel like maybe a viable human being. To go from feeling the possibility of feeling loved in a real way, and having it turn to her feeling like he sees her as another hooker, was one of the big devastations for her.

Was there an inspiration for Lori’s arc in the way there was for Candy and the twins and some others?

Simon: It’s an amalgam of several. But there was an adult actress in the Eighties who we researched, Shauna Grant, who killed herself with a gun. And I actually went to you at the start of the third season and asked if you wanted to get rid of the gun and have her overdose or do something else, because a gun is so shocking. And you went right for it!

Meade: That’s the thing. The through-line for me is that Lori is doing it to herself. Maybe I have to be harsher on her than everyone else is. But to me, she could have gotten out of this. She’s not stupid, and she’s not untalented.

David, is there anything we haven’t discussed that you’d like to say about Lori or Emily?

Simon: It became really exhilarating for the writers. You start acquiring a commitment to the character. You can give Lori a line that’s brutal, almost unrelenting. And you can give her a moment of great vulnerability. And [Emily was] going to execute it. We felt like we had the perfect vehicle for asserting what the cost is.

Meade: It’s been a wild ride.

Simon: The next time we work together, it’s going to be as some really drab bureaucrat. You’ll be the assistant undersecretary for defense, sitting at board meetings all day.

Meade: But tragic!

The series finale of The Deuce airs October 28th.