Chickens and brown hares were introduced to Britain in the 5th century AD and were worshipped as gods rather than eaten, archaeologists claim.

Instead of being seen as food, the creatures were associated with deities, and buried with care and intact, found experts from the University of Exeter.

Archaeological evidence shows no signs of butchery on recently unearthed bones, and the research suggests the two animals were not imported for people to eat.

The study, which also included researchers from Oxford and Leicester universities, looked at how brown hares, rabbits and chickens were introduced to Britain.

The team also wanted to find out exactly how the originally non-native species became incorporated into modern British Easter traditions.

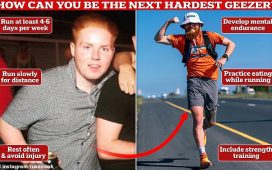

In the earliest days of hares, chickens and rabbits in Britain 2,500 years ago the creatures were treated as gods – buried in individual graves rather than thrown away as rubbish. This is a skeleton of a hare found in Winklebury, Hampshire

The team also wanted to find out exactly how the originally non-native species became incorporated into modern British Easter traditions. Stock image

Bones found at sites in Hampshire and Hertfordshire suggest brown hares and chickens were originally brought to Britain between the 5th and 3rd century BC.

This is much earlier than originally thought. Previous studies had placed their introduction to between the first and second century AD – hundreds of years later.

Researchers say the discovery of buried skeletons fits historical evidence that neither animal was eaten until the Roman period.

Professor Naomi Sykes, from the University of Exeter, said: “Easter is an important British festival, yet none of its iconic elements are native to Britain.

‘The idea that chickens and hares initially had religious associations is not surprising as cross-cultural studies have shown that exotic things and animals are often given supernatural status,’ the lead author said.

“Historical accounts have suggested chickens and hares were too special to be eaten and were instead associated with deities.’

Chickens were originally associated with an Iron Age god akin to Roman Mercury, and hares with an unknown female hare goddess.

‘The religious association of hares and chickens endured throughout the Roman period,’ said Sykes.

She added that archaeological evidence shows that as their populations increased, they were increasingly eaten, and hares were even farmed as livestock.

The animals’ remains were then disposed of as food waste, rather than being buried as individuals – suggesting much less respect over time.

During the Roman period, both species were farmed and eaten, and rabbits were also introduced, researchers say.

In AD 410, the Roman Empire withdrew from Britain causing economic collapse.

Chickens were originally associated with an Iron Age god akin to Roman Mercury, and hares with an unknown female hare goddess

Rabbits became locally extinct, while populations of chickens and brown hares crashed, and due to their scarcity they once again regained their special status.

After the Romans had left Britain, people stopped hunting hares and this may explain why archaeologists have found few remains of the animal until the medieval period.

But chicken populations increased after they were introduced during the Roman period – likely due to sixth century Saint Benedict.

Benedict forbade the consumption of meat from four-legged animals during fasting periods such as Lent – making birds a popular food source.

His rules were widely adopted in the 10th and 11th centuries, increasing the popularity of chickens and eggs as fast-day foods.

Historical and archaeological evidence show rabbits were reintroduced to Britain as an elite food during the 13th century AD.

According to experts, they were increasingly common in the 19th-century landscape, likely contributing to their replacement of the hare as the Easter Bunny when the festival’s traditions were reinvigorated during the Victorian period.